Jan 27th 2011 | from the Economist print edition

COUNTERFEIT drugs can make up around a quarter of all those sold in poor countries, according to some estimates. They provide a lucrative and lethal business, against which most consumers are powerless. “If your anti-malaria pill is made of any old white powder, you may not survive,” says Bright Simons, one of the founders of mPedigree, an advocacy group from Ghana.

COUNTERFEIT drugs can make up around a quarter of all those sold in poor countries, according to some estimates. They provide a lucrative and lethal business, against which most consumers are powerless. “If your anti-malaria pill is made of any old white powder, you may not survive,” says Bright Simons, one of the founders of mPedigree, an advocacy group from Ghana.

Mr Simons is not just fighting with words. Late last year mPedigree launched a mobile service in Ghana and Nigeria that could make a dent in the fake-drug trade. People buying medicine scratch off a panel attached to the packaging. This reveals a code, which they can text to a computer system that looks it up in a database. Seconds later comes a reply saying whether the drug is genuine. The service is paid for by pharmaceutical companies that want to thwart the counterfeiters. Hewlett-Packard runs the computer system and found a cheap way to print the scratch-off labels.

This is just one of many such services mushrooming in poor countries, using mobile-phone technology that once carried only humble voice and text messages. Rohan Samarajiva, the boss of LIRNEasia, a think-tank in Sri Lanka, calls it “more than mobile”. Jussi Hinkkanen, Nokia’s head of policy in Africa, says the mobile revolution is moving “from ear to hand”.

The number of users is still small: even among young people in South-East Asia (a tech-friendly lot) only 8% had used “more-than-voice” services, according to a poll by LIRNEasia. But the potential is exciting. Mobile phones are the world’s most widely distributed computers. Even in poor countries about two-thirds of people have access to one (see chart 1). As a result, such devices and their networks, though mainly still much simpler than in the rich world, have become a platform on which many other services can be built. This boosts innovation—just as smartphones and faster wireless data networks have led to an explosion of mobile applications (“apps”).

The number of users is still small: even among young people in South-East Asia (a tech-friendly lot) only 8% had used “more-than-voice” services, according to a poll by LIRNEasia. But the potential is exciting. Mobile phones are the world’s most widely distributed computers. Even in poor countries about two-thirds of people have access to one (see chart 1). As a result, such devices and their networks, though mainly still much simpler than in the rich world, have become a platform on which many other services can be built. This boosts innovation—just as smartphones and faster wireless data networks have led to an explosion of mobile applications (“apps”).

Classifying mobile services in poor countries is not an exact science. Richard Heeks, director of the Centre of Development Informatics at the University of Manchester, sorts them by their impact on development. One category is services that “connect the excluded”. In their simplest form they provide information to those who would otherwise be out of the loop. Farmer’s Friend in Uganda, for instance, sends out market prices and other agricultural information in text messages.

Such services have been around for some time, but they have become more common—and much more varied. Nokia now provides its Ovi Life Tools, a set of information services from weather to sport, to more than 6m users of its handsets in China, India, Indonesia and Nigeria. Esoko, a Ghanaian “communication platform”, in the words of Mark Davies, its founder, allows two-way communication: people and businesses in 15 African countries can upload their own market or other data, which then become accessible via the internet and mobile phones.

Mobile trading platforms are also in this category. At first most of them focused on agricultural goods: Dialog Tradenet in Sri Lanka lets farmers check market prices and text in offers, helping them to time their harvest to maximise income. But many, including Dialog Tradenet, have other things on offer. In India, Babajob.com lists low-skilled jobs. The most popular items on CellBazaar in Bangladesh are second-hand mobile phones. For people with some cash to spare, KenyaBUZZ, one of the larger local websites in east Africa, is selling tickets for cultural and sports events over the phone.

Mobile phones can also spread learning. In Bangladesh the BBC World Service Trust sponsors a service called BBC Janala that allows people on a few dollars a day to improve their English. After dialling “3000”, they can listen to hundreds of English lessons and quizzes, updated weekly. Mobile operators charge about two cents for each three-minute lesson. Since BBC Janala was launched in November 2009, 3.1m people have used it.

Researchers in South Africa working for SAP, a software giant, are trying to connect very small businesses, which make up a large part of Africa’s economy. One service lets craftsmen create a virtual job docket with a few texts or touches on a smartphone, even without mobile-network coverage. The information is uploaded to a computer system later. Another allows rural stores to order goods, saving time-consuming trips to city markets.

A second category of services includes those that cut out the middleman, or at least keep tabs on him. This is especially helpful in using government services. In the Indian state of Karnataka, corrupt officials would often demand a bribe before issuing landownership certificates, which farmers need, for instance, to obtain a loan. The Bhoomi project helps them directly, by using the internet and mobile phones.

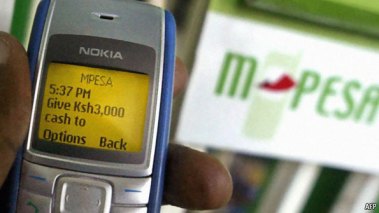

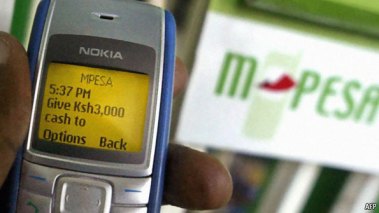

Disintermediation is also made possible by mobile money. Services to transfer cash by text message have been around for some years. One of the most successful, M-PESA, began in 2007 in Kenya, where it now has more than 13m users. It is now used for salaries, bills, donations: few things cannot be paid for via a handset. Similar services can be found in more than 40 countries. Though not yet on the same scale, this seems to be only a question of time: in most countries in sub-Saharan Africa, more people have a mobile phone than a bank account (see chart 2).

Other firms are extending the reach of mobile money. Software developed by Tagattitude, a French start-up, uses a handset’s sound channel to transmit money and will be used by several banks in Africa. A Little World, an Indian firm, has combined several pieces of technology to create a “branchless microbanking system” to allow people in remote areas to withdraw cash. A fingerprint reader identifies them and the sum is deducted from their accounts via a special handset. A small printer produces a receipt. The system already has more than 3m users in India. In Andhra Pradesh it directly disburses welfare payments and pensions.

Other firms are extending the reach of mobile money. Software developed by Tagattitude, a French start-up, uses a handset’s sound channel to transmit money and will be used by several banks in Africa. A Little World, an Indian firm, has combined several pieces of technology to create a “branchless microbanking system” to allow people in remote areas to withdraw cash. A fingerprint reader identifies them and the sum is deducted from their accounts via a special handset. A small printer produces a receipt. The system already has more than 3m users in India. In Andhra Pradesh it directly disburses welfare payments and pensions.

Money on the move in Kenya

The sound of the crowd, texting

A third, perhaps even more promising category is “crowdvoicing”. Ushahidi, founded by a group of activists in Kenya, is among its pioneers. After the country’s disputed elections in 2008, Ushahidi (which means “testimony” in Swahili) mapped reports about violence, most of them text messages, on a website. Now the organisation offers software and even a web-based service to monitor anything from elections to natural disasters. Similarly, text-messaging software called FrontlineSMS collects and broadcasts information.

Such techniques are increasingly applied in other areas, particularly health. Stop Stock-outs, another African group, has used Ushahidi to map where essential medicines are sold out. By checking whether a drug is genuine, users of mPedigree and another Ghanaian service called Sproxil provide real-time data about which illnesses are on the rise (and can be sent more information as needed). In Mali a company called Pesinet gets agents to send in the weight of newborn babies. If the figure falls below a certain level, the baby is examined more closely.

Then there is txteagle, which hopes to reward those willing to perform small jobs on a mobile phone. Its founder, Nathan Eagle, discovered that nurses in Kenya were much likelier to text in the stock levels at their blood banks if they were compensated with a bit of airtime. This got him thinking about whether other tasks could be “crowdsourced” in this way. Today firms use txteagle for translating words into a local dialect and checking street signs for a satellite-navigation service. Mr Eagle hopes that the service will spread far, in particular to Asia.

A fourth and last category hardly exists yet, but could prove the most important, says Mr Heeks: platforms that allow the world’s poor to “appropriate the technology and start applying it in new ways”. One small example is “beeping”: hanging up after a single ring. First used to signal that someone wants to be called back because of lack of credit, it has become a free messaging system. In some countries, street hawkers assign special ringtones to different customers, which are in effect free messages placing orders.

In rich countries, online stores for smartphone apps gave digital innovation a boost. LIRNEasia’s Mr Samarajiva hopes that something similar will happen in the poor world. An early example is AppZone in Sri Lanka. It allows developers to create, test and sell applications, while operators promote them to their customers.

The list will certainly get longer. Whether such services will be commercial successes is another question. Having looked at 400 mobile businesses, the Monitor Group, a consultancy, concludes that too many are dependent on donor money. Social entrepreneurship often muddles demand and need, says Jan Schwier of Monitor. The fact that an African smallholder needs prices for his crops on his mobile does not mean he will pay for them.

Not many services are set up to grow, says Brooke Partridge of Vital Wave Consulting, which advises businesses in emerging markets. Providers lack technology, money and market knowledge. “We don’t need more new services, but a better focus on commercialisation,” she says.

For others bureaucracy, taxation and bad regulation are the obstacles. In many African countries providers of new mobile services cannot deal with network operators directly, but must use intermediaries to get, for instance, a short code for customers to dial. Governments also use mobile networks as cash cows. A study in 2008 by the GSM Association, an industry group, found that the ratio of mobile-related tax to operators’ revenues in sub-Saharan Africa was 30%. Today the share is probably even higher. And regulators often limit competition, for instance by failing to license radio spectrum to new entrants. All this means that mobile communications are more expensive than they need be. “Price remains the major barrier to the growth of mobile entrepreneurship in Africa,” says Steve Song, a telecoms expert at the Shuttleworth Foundation, a think-tank in South Africa.

Talk of a “Development 2.0”—meaning a mobile-driven transformation of how poor countries develop—thus seems premature. But the potential of mobile services should not be underestimated. If they take off, they could transform lives and livelihoods, not just by connecting the world’s poor to the infrastructure of the digital economy, but by allowing them to become digital producers and innovators.

Fanciful? Maybe, but sceptics said the same about the potential of mobile phones in poor countries a decade ago. Just think what would be possible if smartphones and even tablet computers become as cheap and common in poor countries as mobile phones are today.

via Mobile services in poor countries: Not just talk | The Economist.

Other firms are extending the reach of mobile money. Software developed by Tagattitude, a French start-up, uses a handset’s sound channel to transmit money and will be used by several banks in Africa. A Little World, an Indian firm, has combined several pieces of technology to create a “branchless microbanking system” to allow people in remote areas to withdraw cash. A fingerprint reader identifies them and the sum is deducted from their accounts via a special handset. A small printer produces a receipt. The system already has more than 3m users in India. In Andhra Pradesh it directly disburses welfare payments and pensions.

Other firms are extending the reach of mobile money. Software developed by Tagattitude, a French start-up, uses a handset’s sound channel to transmit money and will be used by several banks in Africa. A Little World, an Indian firm, has combined several pieces of technology to create a “branchless microbanking system” to allow people in remote areas to withdraw cash. A fingerprint reader identifies them and the sum is deducted from their accounts via a special handset. A small printer produces a receipt. The system already has more than 3m users in India. In Andhra Pradesh it directly disburses welfare payments and pensions.

y, an invitation from the Esoko blog managed to get me to focus and write something coherent on MIS topics again. I am re-posting the sections, other than the introduction. If you are reading this, you’d know who I am.

y, an invitation from the Esoko blog managed to get me to focus and write something coherent on MIS topics again. I am re-posting the sections, other than the introduction. If you are reading this, you’d know who I am.